… grows to a maximum length of only 24 mm and this puts it in the company of the smallest vertebrates on earth. Imagine how small its heart must be, pumping the lifeblood that sustains its tiny form. The food it eats must be smaller still, and how tiny its offspring must be after delivery?

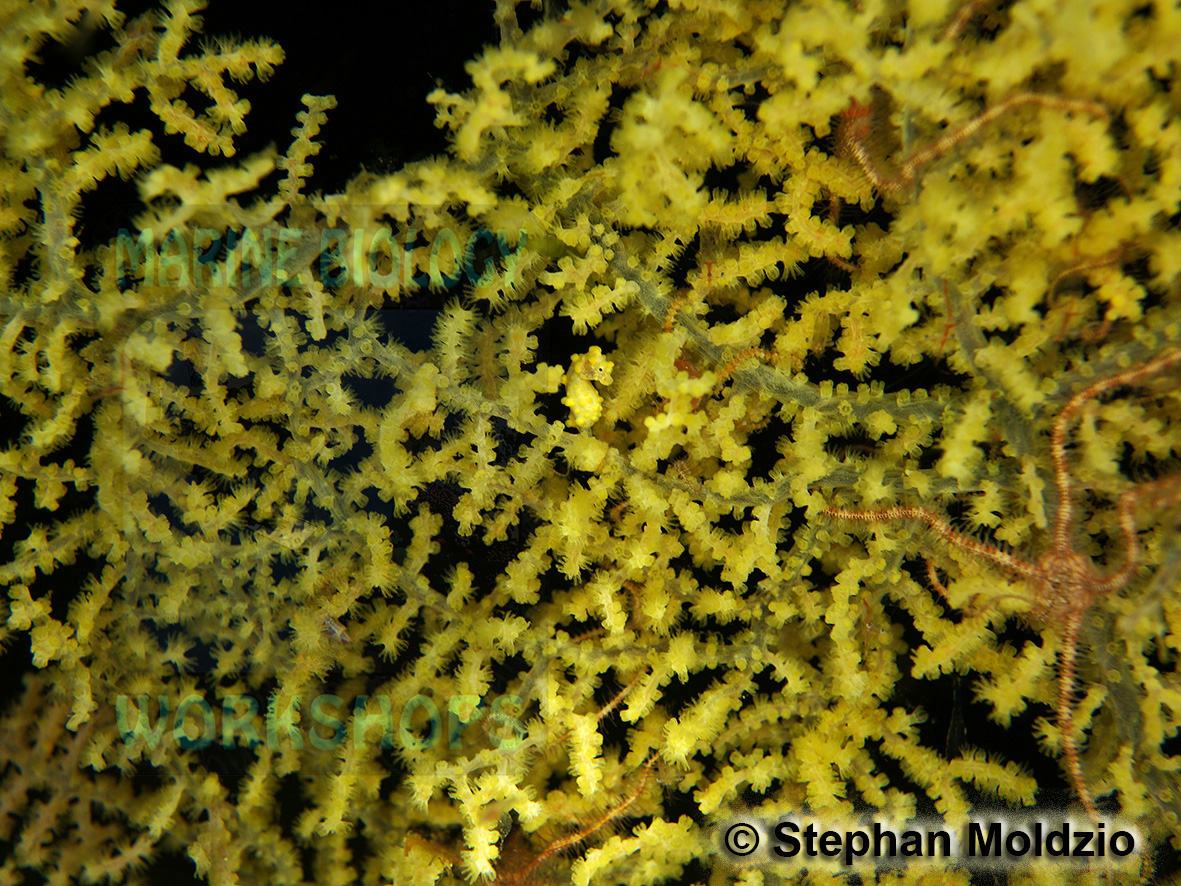

Hippocampus bargibanti lives in sea fans, genus Muricella, at exposed sites with strong currents mostly below 20 m depth and they are perfectly adapted to their hosts. These specimen are really extremely hard to find as they are not very abundant and they do not even inhabit all suitable gorgonians. Mimesis – the natural ability of certain organisms to invoke an environment-specific camouflage is well documented in many marine organisms such as the frogfish and scorpionfish. The Pygmy seahorse though, has truly honed this to perfection: This is quite likely the reason this species was only discovered in 1970 rather accidentally.

Hippocampus bargibanti occurs in three colour morphs, pink, yellow and orange, and they live in Muricella sea fans with just the same colour.

The genus Muricella currently consists of 35 described species, and it is impossible to determine the species accurately based only on photographs. However, available literature has described pink-coloured seahorses living in Muricella plectana, while yellow and orange-coloured seahorses were found in Muricella paraplectana. The seahorses’ body resembles the coenenchyme tissue of the branches of the sea fan, whereas the wart-like tubercles resemble the RETRACTED polyps of the sea fan. Actually the seahorses´ camouflage is better when the seafans´ polyps are retracted, rather than with open polyps. When a sea fan is disturbed, e.g. by a potential predator, resulting in the retraction of the polyps, the seahorses visually merges into the sea fan thereby ensuring its safety.

Apart from H. bargibanti, seven additional species of pygmy seahorses have been indentified, ranging in length from 13 to 30 mm.

Many divers and UW photographers have been searching for more species worldwide after a new species was described in 2002: H. denise (Lourie & Randall, 2002), followed by H. colemani (Kuiter, 2003), H. severnsi (Lourie & Kuiter, 2008), H. pontohi (Lourie & Kuiter, 2008), H. satomiae (Lourie & Kuiter, 2008), H. waleananus (Gomon & Kuiter, 2009) and H. debelius (Gomon & Kuiter, 2009).

Scientists believe there are more species that have yet to be found and described.

Hippocampus bargibanti has the widest occurrence of all Pygmy seahorses: from Japan to Queensland and eastwards to Vanuatu.

It feeds on zooplankton, which it likely cannot take up directly from the water. The plankton particles likely need to be first caught by the sea fans’ polyps, thereafter, they get picked up by the seahorse. These tiny creatures have to feed continuously to survive. Another feature is that its gills are fused behind the head. Until recently, only sparse and often uncertain information was available for H. bargibanti. It was unclear if the juveniles of these animals may adapt to the colour of their host coral, or if their colour is determined genetically, meaning that the pink, yellow, or orange coloured seahorses need to search for a suitable coloured coral.

Also, it was questioned if their reproduction biology is similar to other seahorses, i.e. the female lays its eggs in a fold of the males’ belly where the eggs are being fertilized and brooded until the offspring are released. However, once released, how do the baby seahorses drift to other sea fans? Do these juveniles settle down after their planktonic stage on various substrates, before they go to their Muricella sea fan? These assumptions and questions needed verification and answers. Aquarium observations have contributed a lot to what we know about the life, behaviour and reproduction of seahorses. Several species are being bred even by hobbyists regularly.

An attempt by the Waikiki-Aquarium, Hawaii, in 2003 in keeping the Pygmy seahorse unfortunately failed due to the decline of the coral host.

The aquarium biologists Charles Delbeek and Norton Chan concluded that the stable keeping of Muricella was the crucial prerequisite for the successful keeping of the Pygmy seahorse. Then, in June 2014 a breakthrough was achieved. After development of a suitable aquarium setup and feeding regime and 3 years of successful keeping of Muricella in a special tank for azooxanthellate corals, a pair of H. bargibanti was introduced at Steinhard Aquarium, San Francisco in May 2014. Four weeks later, the biologists Richard Ross and Matt Wandell succeeded in rearing H. bargibanti.

The courting ritual that began every morning, the mating of the pair in which the female lays the eggs into the males’ belly, as well as the birth of the small seahorses have been filmed and documented (see links below). Every 14 days, an estimated 10 to 70 young are released.

After birth the young are around 5 mm in length and they have been reared in round tanks being fed with copepod nauplii and later, Artemia nauplii. The planktonic life stage of the juvenile seahorses lasts 18 days before they settle down on their host coral. It was then observed that yellow H. bargibanti that live on a yellow Muricella sea fan can produce young which may settle down on a pink sea fan and adopt a pink colour, which nicely resolves the question of does the seahorse choose a home that matches its colour or does it change its colour to match its home.

© Stephan Moldzio / Marine Biology Workshops (2015)