Reef Check EcoDiver Course

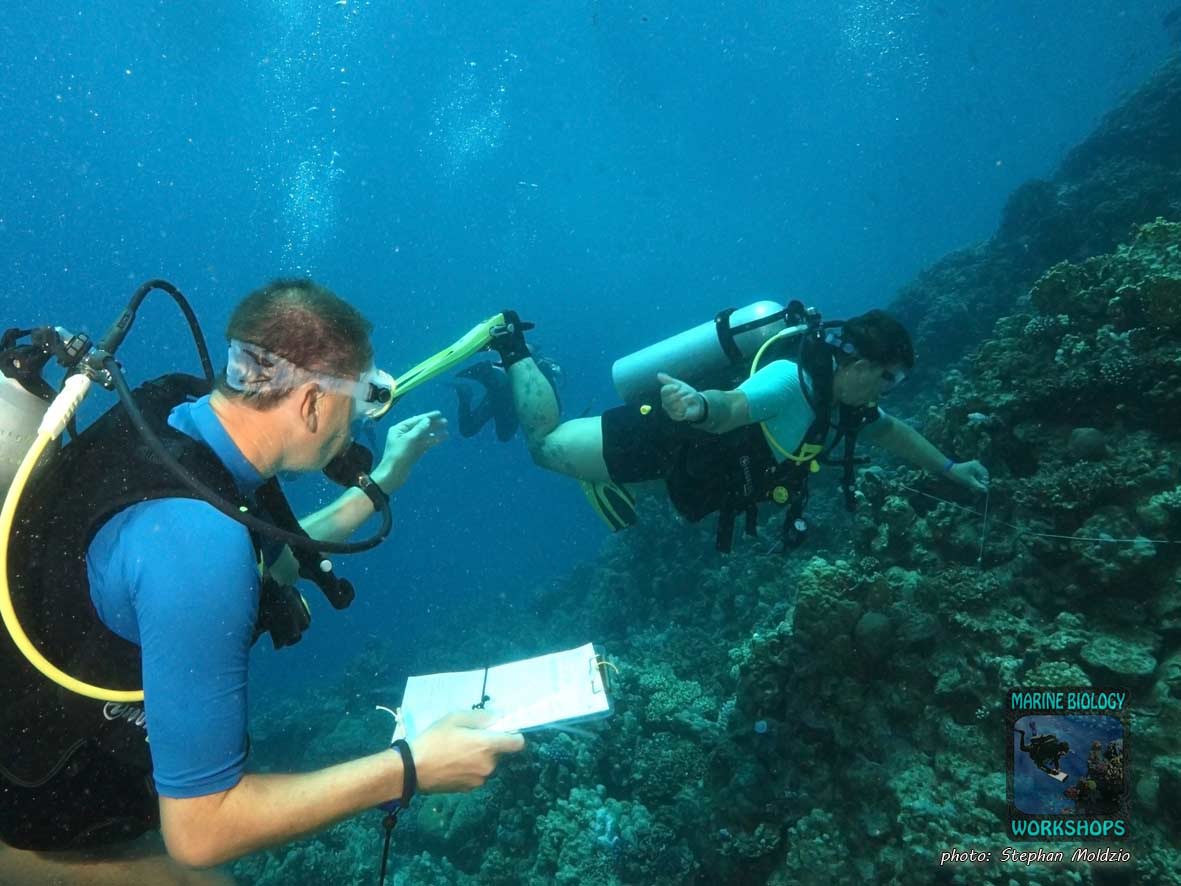

- Citizen Science – participation in reef surveys

- Collecting scientific data

- Raising awareness of human impacts

- Protecting coral reefs

The course was fully booked — 14 participants from five countries: Germany, Poland, Czechia, England, and Egypt. The course language was English. To facilitate understanding of the key content, the Reef Check indicator organisms were translated into the respective languages.

The program included four presentations on the Reef Check method and the three different surveys:

- Fish

- Invertebrates and human impacts

- Substrate

Every day, two training dives took place to practice identifying the Reef Check indicator organisms and to learn the UW hand signals. During the “Beach Exercise,” we practiced the Reef Check method and the exact survey procedure. Afterwards, we conducted a test survey in the reef along a transect of only 20 meters.

Finally, identification tests of the indicator organisms were also on the schedule.

All participants successfully completed the training dives and tests and are now certified Reef Check EcoDivers. They can now help collect scientific data on the condition of the reefs.

International Reef Check Team

Our international Reef Check survey team consisted of a total of 18 people this year. In addition to the course participants, there were also four other divers on-site who had already completed the course in previous years. They wanted to participate in the surveys again and help collect data. Therefore, we had to rotate a bit so that everyone could take part in several surveys. The atmosphere was fantastic — especially because we had such a mixed and international team!

Reef Check Surveys on a total of six reefs

Following the course, we conducted six complete surveys along two depth contours at the following reefs:

- Marsa Shagra north & south

- Abu Nawas Garden

- Sharm Abu Dabab

- Marsa Nakari north & south

We reached the survey sites by Zodiac. First, a buddy team laid out the transect lines at both depth contours, at 3.5 m and 8.5 m. Then the three teams began their surveys!

Everything ran smoothly — first the fish team, then the substrate team, and finally the invertebrate team. After completing the survey, a buddy team retrieved the lines and we returned. In the evening, we entered the data from the underwater slates into the Reef Check Excel sheets.

On one evening, Stephan also gave a public presentation for all guests about Reef Check and our reef monitoring program with Red Sea Diving Safari.

Results of our Reef Check Surveys

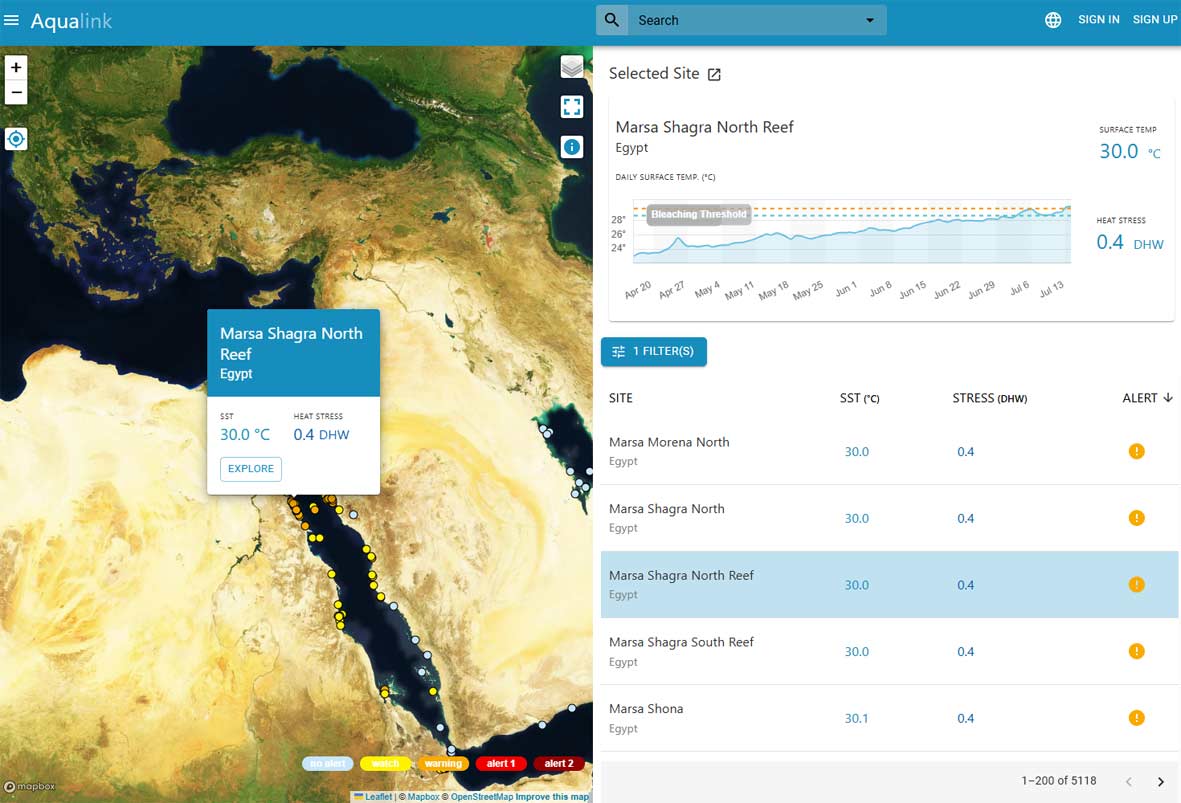

Our collected data were sent to the Reef Check HQ, reviewed once more, and have now been entered into the international Reef Check database:

https://www.reefcheck.org/global-reef-tracker/

A first glance at our data gave us a foretaste:

The 4th Global Coral Bleaching Event 2023–2024 had also taken its toll on our survey sites.

Later, the data was compared with those of previous years, e.g. 2021 oder 2023, what supported this impression.

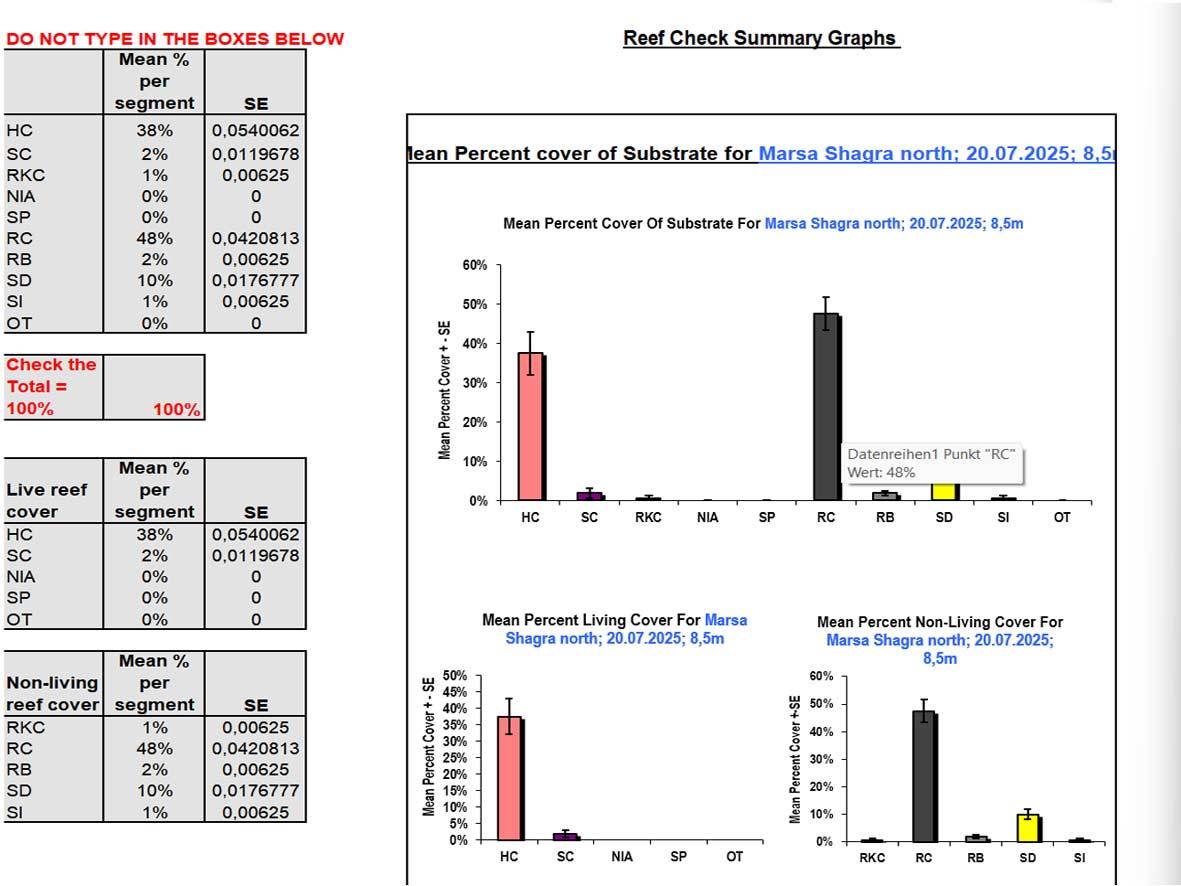

Example Marsa Shagra North Reef and South Reef:

Since the start of our reef monitoring program with Red Sea Diving Safari in 2009, we have conducted surveys every two years at the two reefs of Marsa Shagra. This year was the 9th time.

To illustrate the impact of the coral bleaching events of 2023 and 2024 on the house reef of Marsa Shagra, we were able to compare our 2025 data with those from July 2023:

The average coral cover (hard and soft corals) along our two transects at 3.5 m and 8.5 m depth at Marsa Shagra North Reef decreased from an absolute 63.1% in July 2023 to now 37.5% in July 2025. This corresponds to an absolute decline of 25.6% and a relative decline of 40.6%.

At Marsa Shagra South Reef, the average coral cover (hard and soft corals) decreased from an absolute 56.6% in July 2023 to 42.5% in July 2025. Here, the relative decline was only 25%.

Of course, methodological errors must also be considered.

Although the decline appears drastic, it is still within the mid-range when compared with other places worldwide, or even within the Red Sea.

The Global Bleaching Event 2023 and 2024

Global warming and the resulting warming of the oceans pose an existential threat to coral reefs. The year 2024 was the warmest year since climate records began, surpassing the previous record set in 2023.

To date, there have been four global coral bleaching events.

The first two global bleaching events occurred in 1998 and 2010.

The third, longest, and most extensive Global Coral Bleaching Event (GCBE3) took place from 2014 to 2017: around two-thirds of the world’s reef areas experienced heat stress that led to coral bleaching and coral mortality. Now, during the 4. Global Coral Bleaching Event (GCBE4), from January 2023 to September 2025, 84.4% of the world’s coral reef regions were affected by heat stress that caused coral bleaching.

Severe bleaching was documented in at least, 83 countries and territories.

The global impacts varied by region — some were hit particularly hard, while others were less affected. In the summer of 2024, the Red Sea also experienced its most severe coral bleaching event on record.

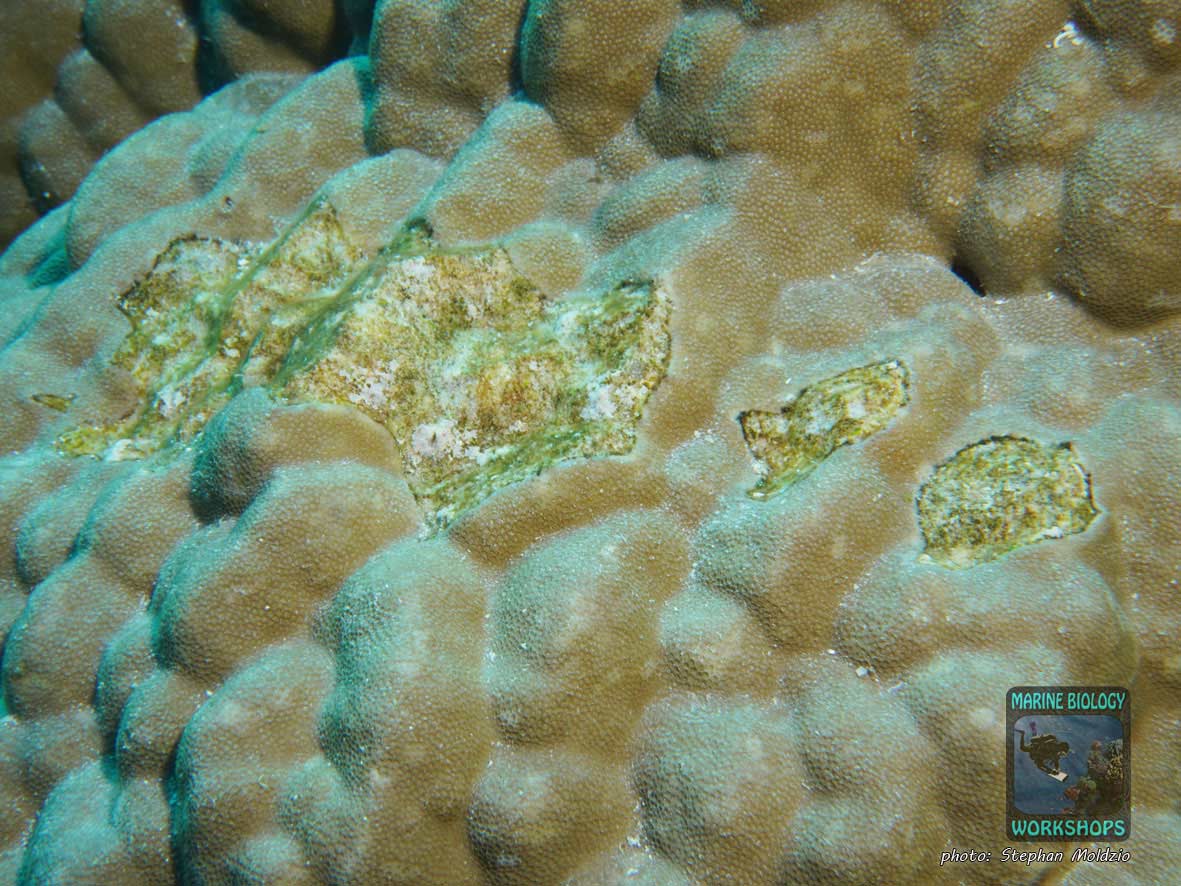

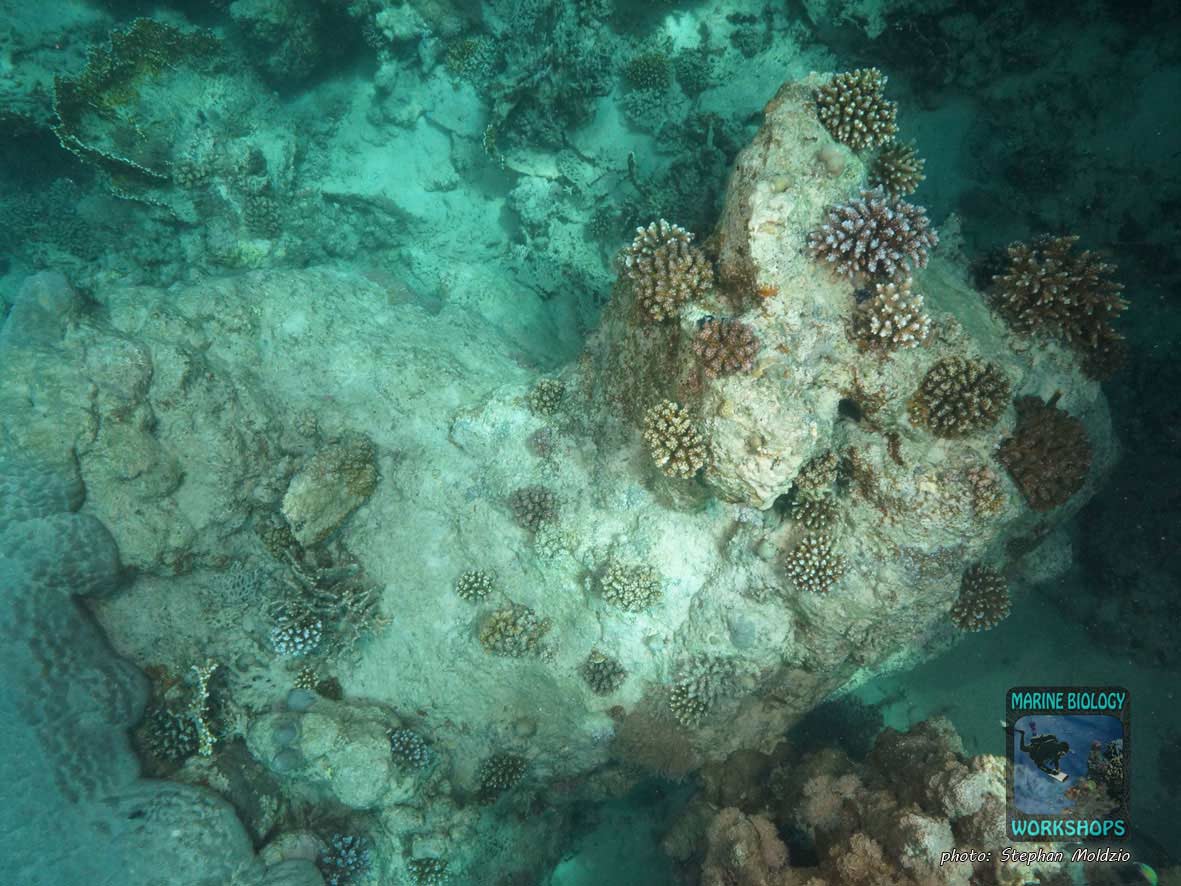

Damaged Corals

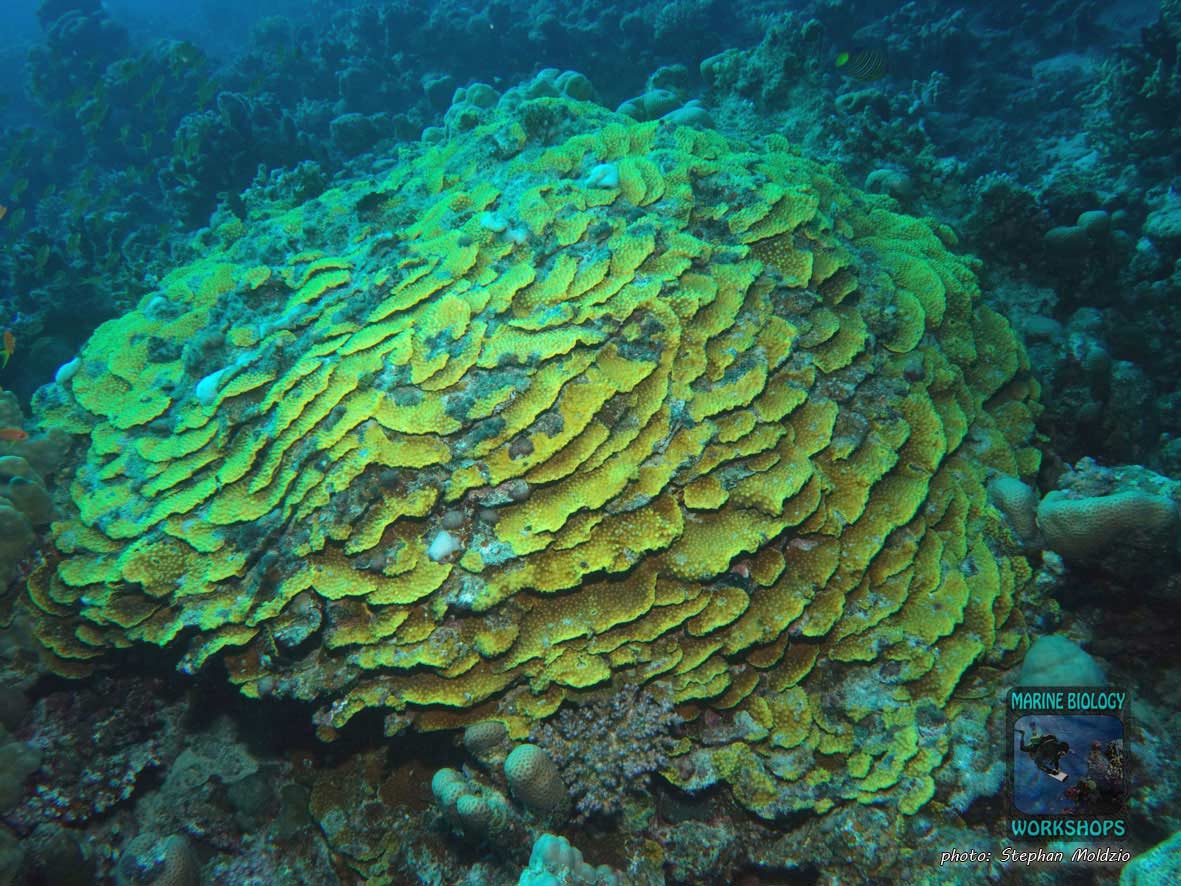

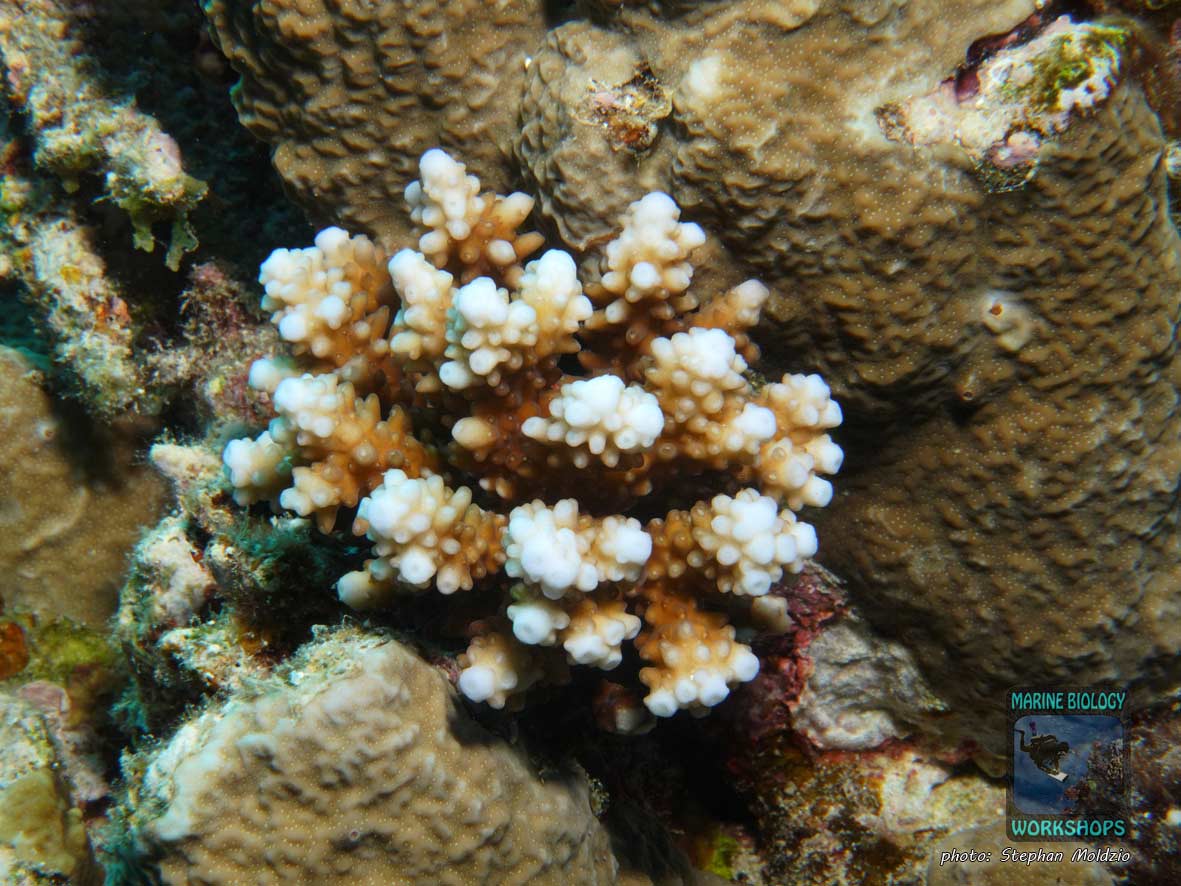

Many corals are damaged or have died, especially in sheltered areas and in shallow water or on the reef flat. But many corals have also survived:

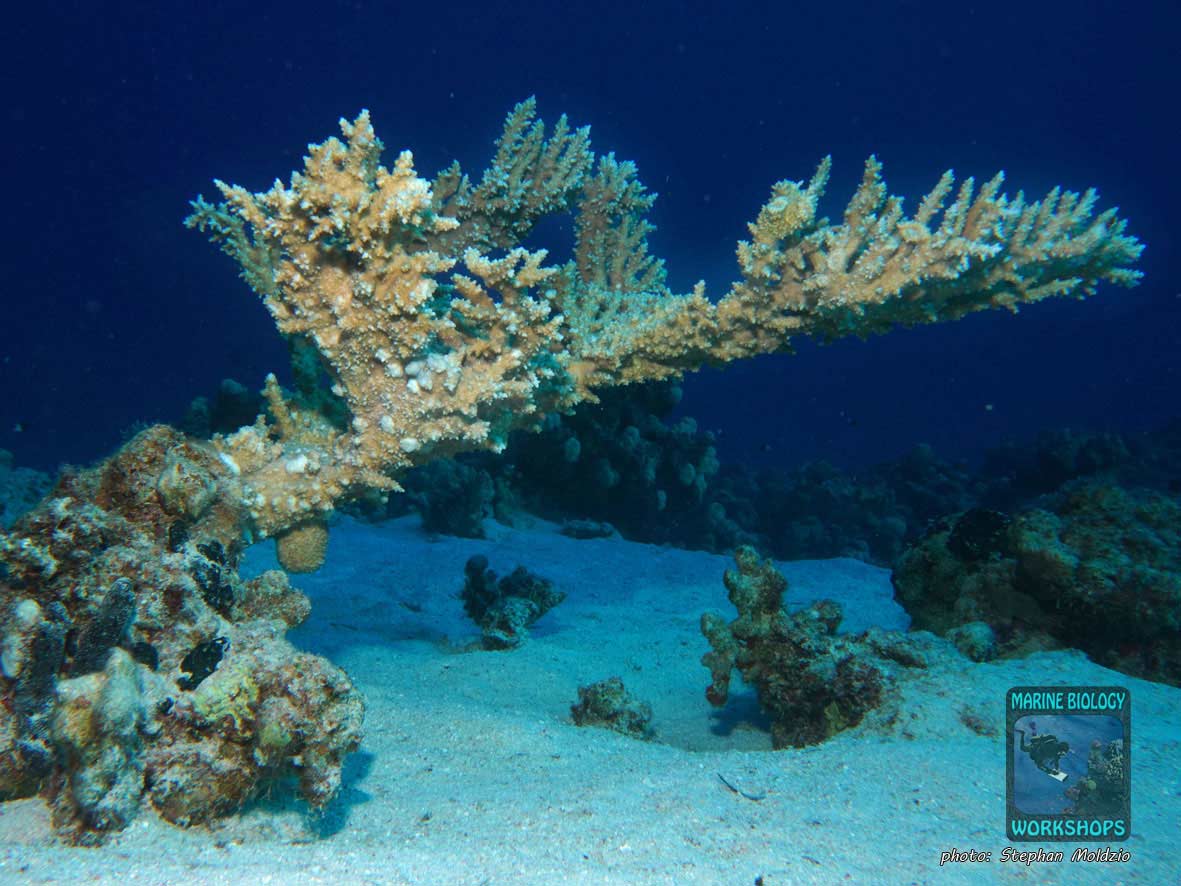

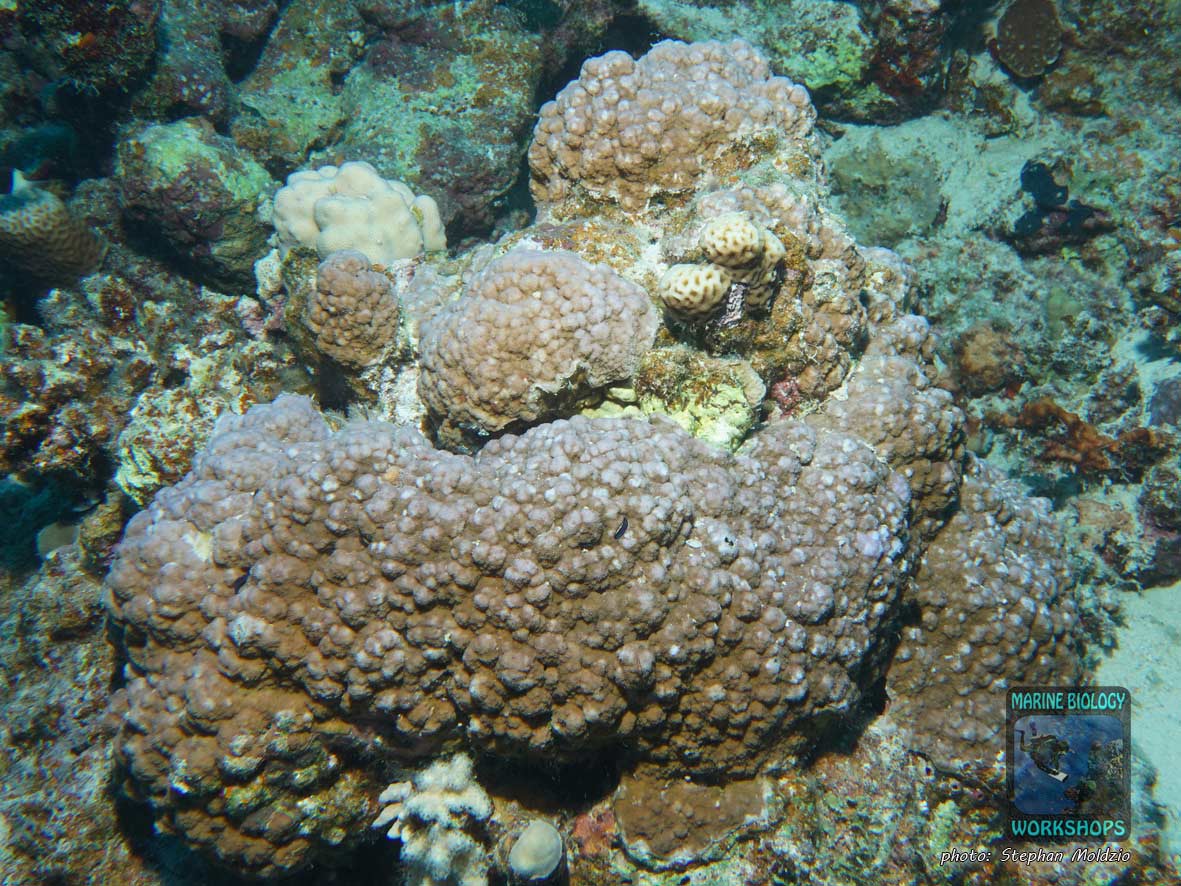

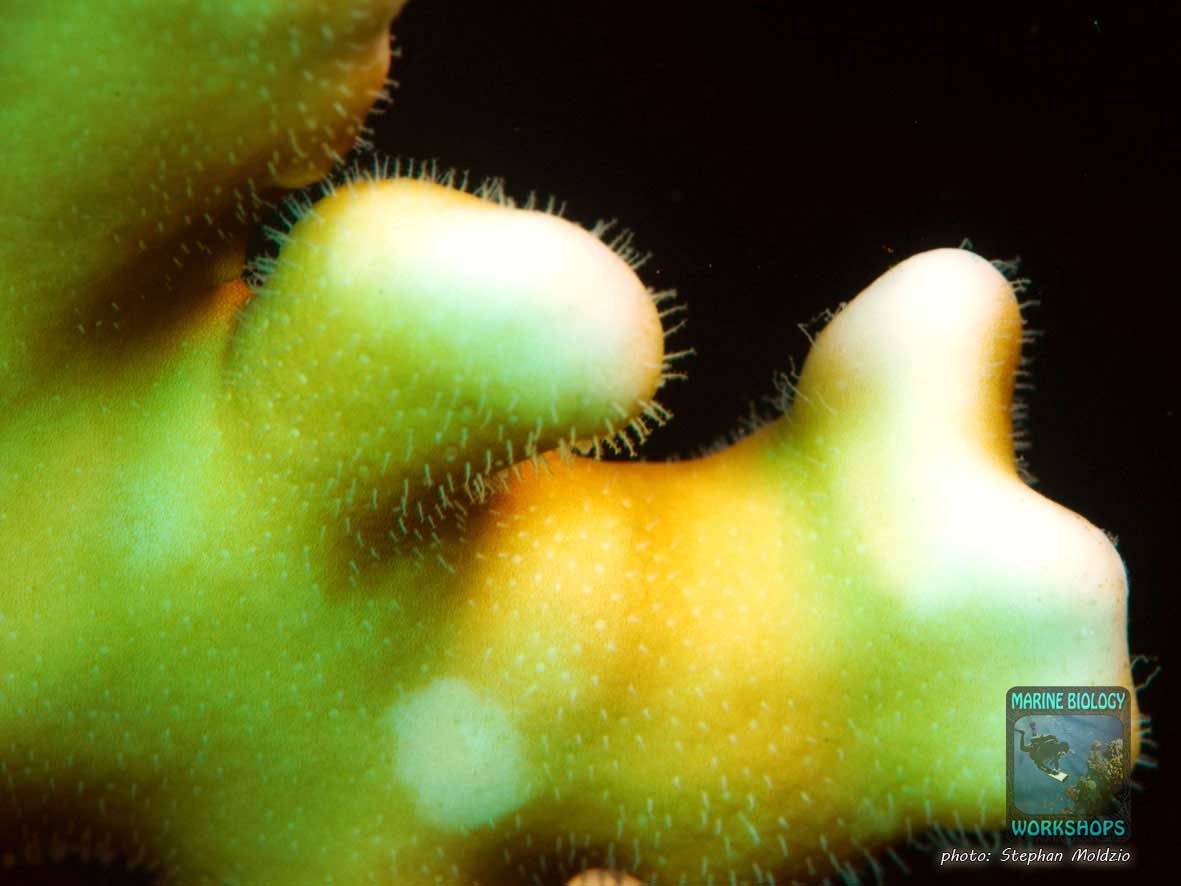

- Many coral colonies have fully recovered from the bleaching and have now shown strong growth since their recovery beginning in autumn of last year.

- Many coral colonies have only partially died on the light-exposed parts of the upper surface. The surviving part in the shaded areas is growing back.

- Even in coral colonies that have almost completely died, a small part often survives and grows back.

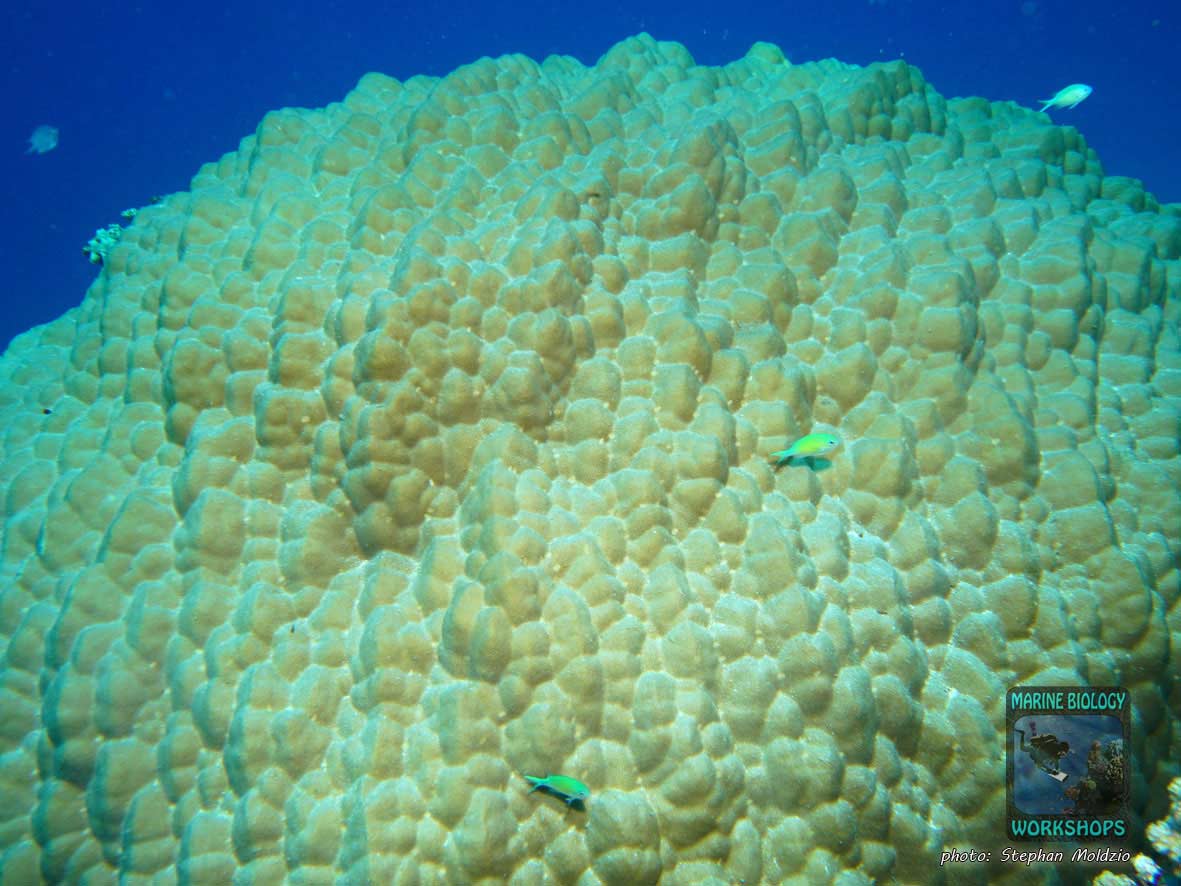

Healthy Corals and Strong Growth

In July 2025, during our Reef Check course and the subsequent surveys, we observed on the one hand the damage caused by the coral bleaching of the previous two years, but on the other hand also the recovery of the corals since then.

First, it should be noted that we observed practically no coral bleaching in July. According to NOAA Coral Reef Watch data, almost no heat stress was present in July; it only began to build gradually over the course of August.

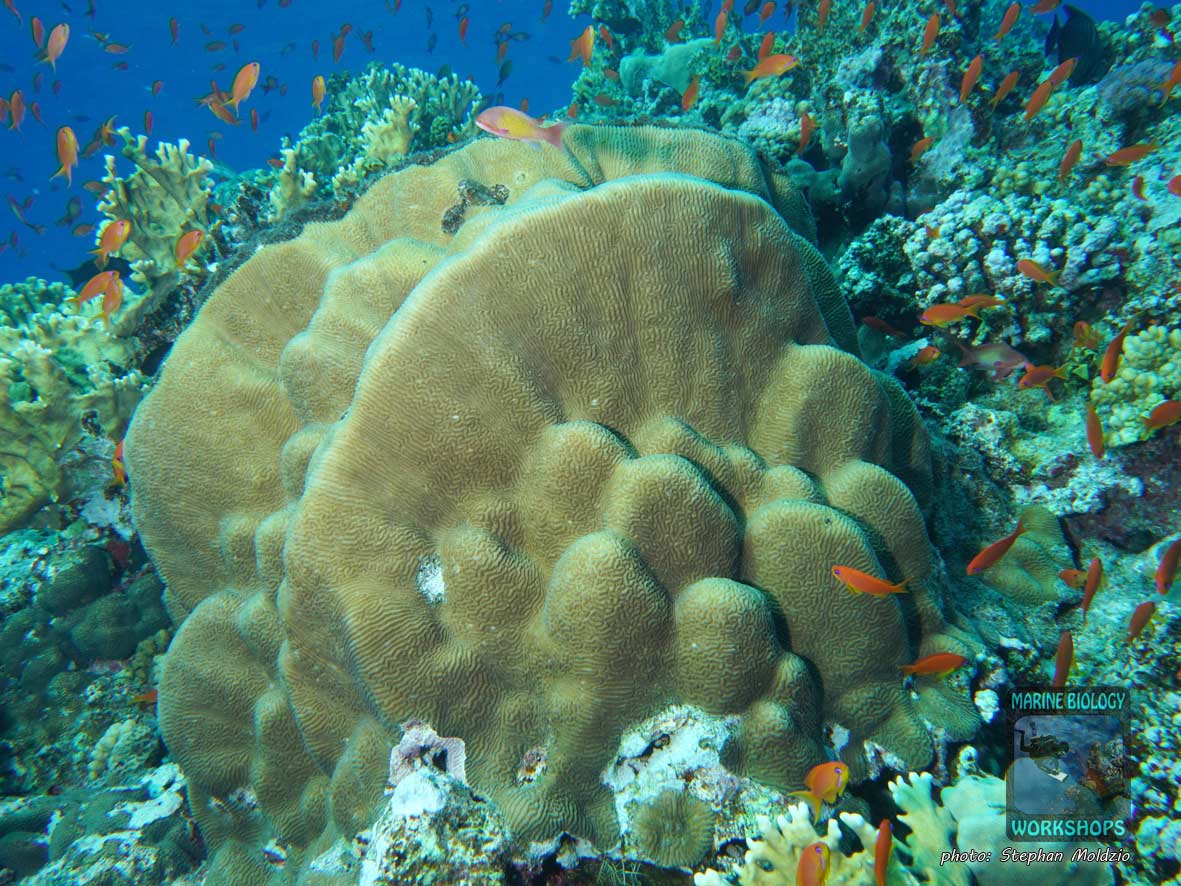

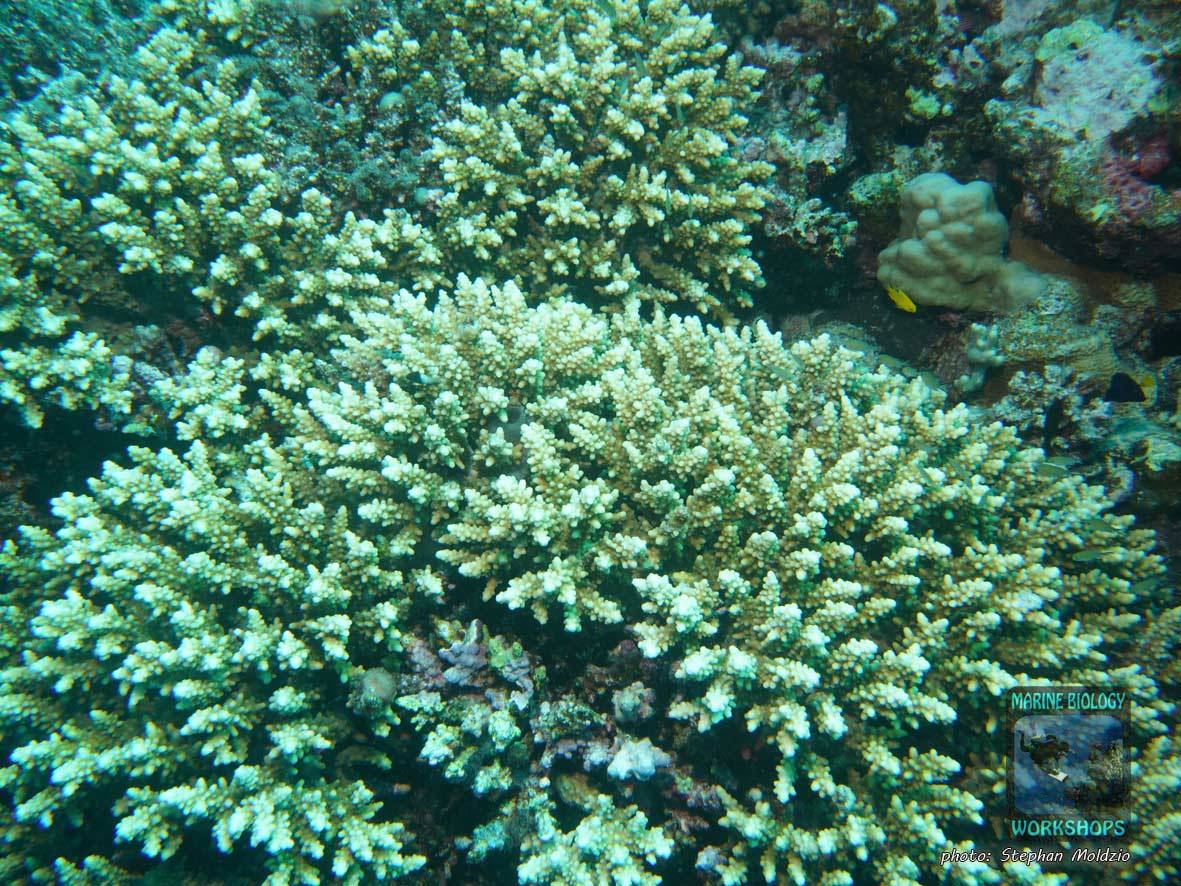

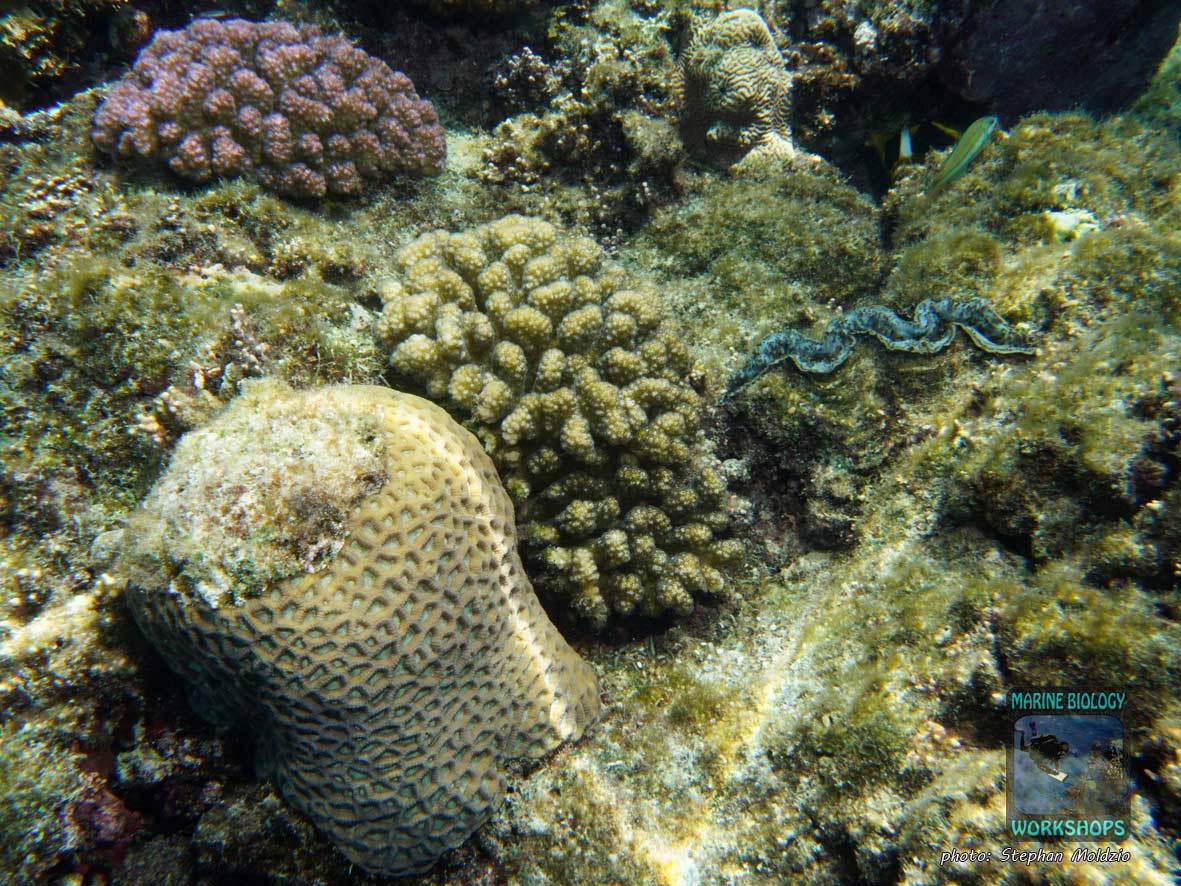

Most corals from various genera appeared healthy, were relatively dark in color, and the bright edges or tips indicated active growth.

All genera and species that can normally be found in Marsa Shagra were also present. However, some genera appeared to have suffered more from the previous coral bleaching, including the fire corals Millepora and the small-polyp stony corals Acropora, Seriatopora, Stylophora, and also Porites, which obtain most of their nutritional needs through their symbiotic zooxanthellae.

The various soft corals, e.g. Xenia spp., Anthelia spp., Sarcophyton spp., were also noticeably reduced in abundance. But since they do not form calcareous skeletons, they disappear without a trace after dying. The small-polyp stony coral Pocillopora, as well as most large-polyp stony corals — which obtain a larger share of their nutritional needs by capturing plankton — were obviously more resilient.

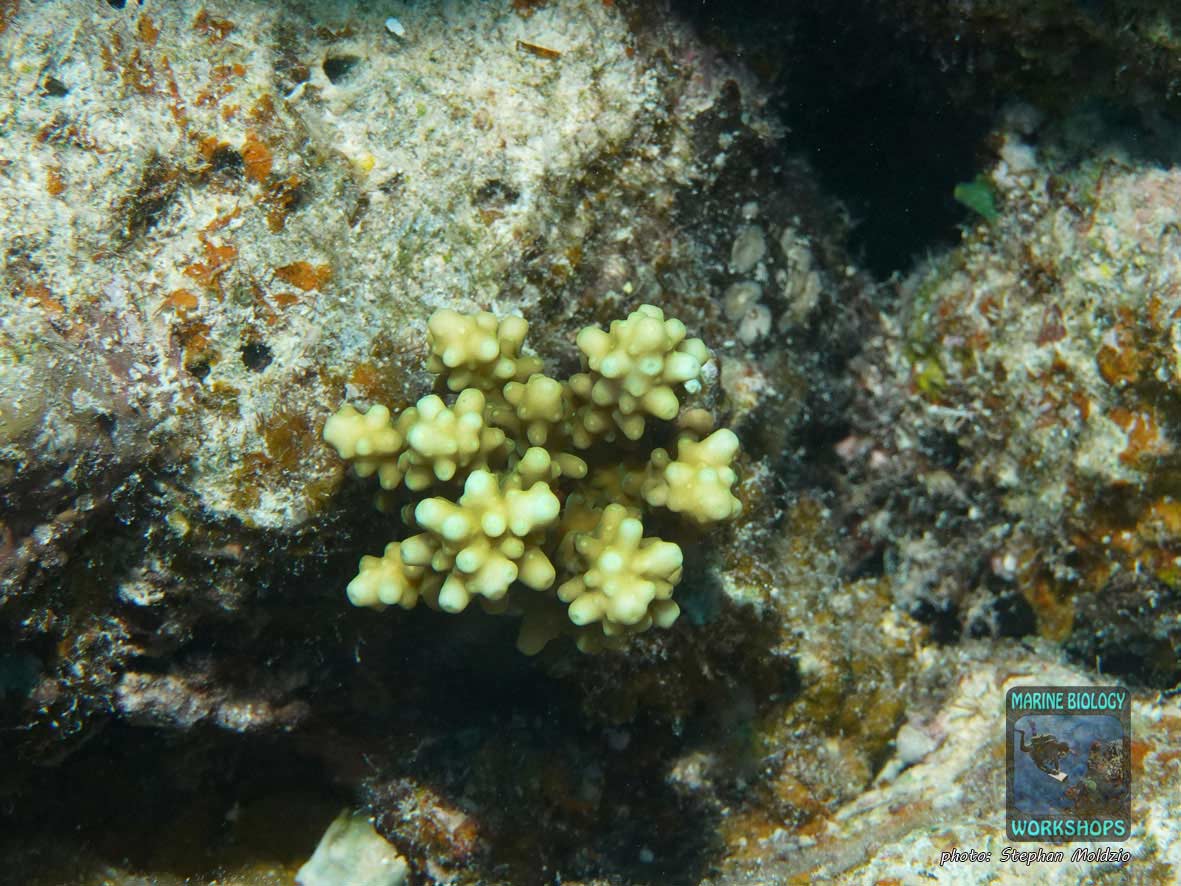

A new Generation of young coral recruits

Also encouraging are the many young coral recruits, which presumably originated from the last coral spawning in April/May of last year: The´re now about one year old. Here, the next generation of corals is growing, which has already survived 2024, the year with the highest heat stress recorded so far.

This also demonstrates that sexual propagation is still going strong in the area.

Although Sea Surface Temperatures in 2025 were also significantly warmer compared to the long-term average, the heat stress was much lower than in 2024. This gives the corals a “breathing space” for further recovery until at least summer 2026, and it is to be hoped that the coming year will also be somewhat cooler. By the time we conduct our next Reef Check surveys in summer 2026, the corals will have grown and the reef will have continued to recover.

The big question for the future is whether and how corals, and which species, can adapt to long-term rising temperatures. There is certainly a selection process occurring in this respect. Certain species or genotypes that cannot cope with higher temperatures will disappear, while others will continue to withstand them.

Algae – the winners of the climate crisis

The “winners” of coral bleaching are various algae that occupy much of the freed-up substrate, including the dead coral skeletons. Filamentous coralline algae (Amphiroa spp.) have experienced a real boost, having previously been rather rare or hidden. Various brown algae species, such as Turbinaria and Padina, appear to have increased notably, particularly on the reef crest. Similarly, gelatinous cyanobacteria, which have hardly any predators, have increased noticeably.

Abundance of fish at Marsa Shagra

The house reef of Marsa Shagra has been effectively protected for over 35 years; no fishing takes place here. As a result, many large fish are regularly encountered: schools of snappers, large groupers, which have already become rare elsewhere due to overfishing. A variety of herbivorous fish, particularly parrotfish, surgeonfish and rabbitfish, graze continuously on filamentous and green algae, including many juvenile individuals. The many different species of butterflyfish also indicate a healthy coral reef. Many of them are food specialists. Most of the fish shown here are also indicator organisms for the Reef Check method.

Diversity of invertebrates

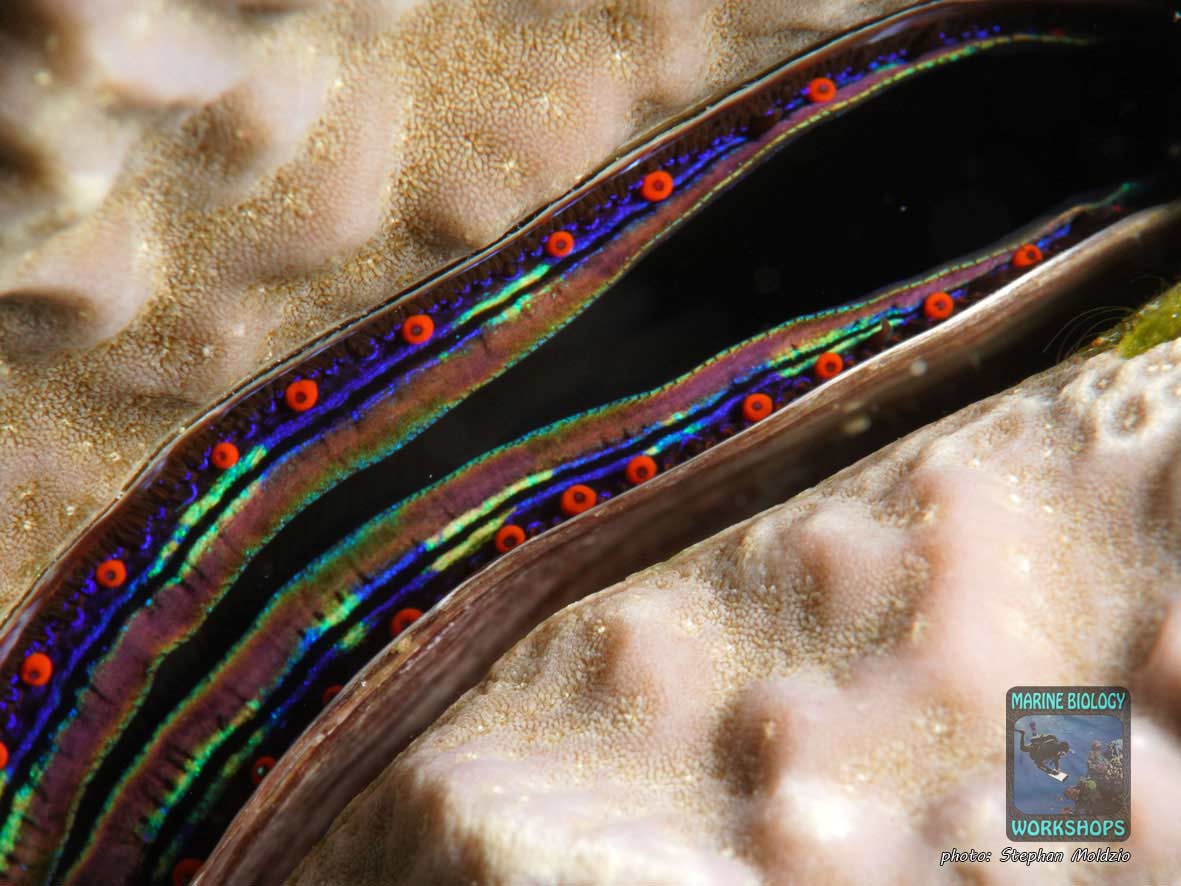

During our dives at Marsa Shagra, we also encountered a wide variety of invertebrates from various groups: crustaceans, echinoderms, mollusks, sponges, hydrozoans, jellyfish, polychaetes, and flatworms.

Among the mollusks (Mollusca), we observed a wide range of nudibranchs and shelled snails, reef mussels, scallops, as well as reef octopus and reef squids.

Among the jellyfish, we encountered the elegant blue jellyfish (Cephea cephea), which is often attacked by various butterfly and surgeonfish and practically eaten alive.

If you would like to learn more about this world of the coral reef and its many interconnections, we highly recommend our Marine Biology Workshops.

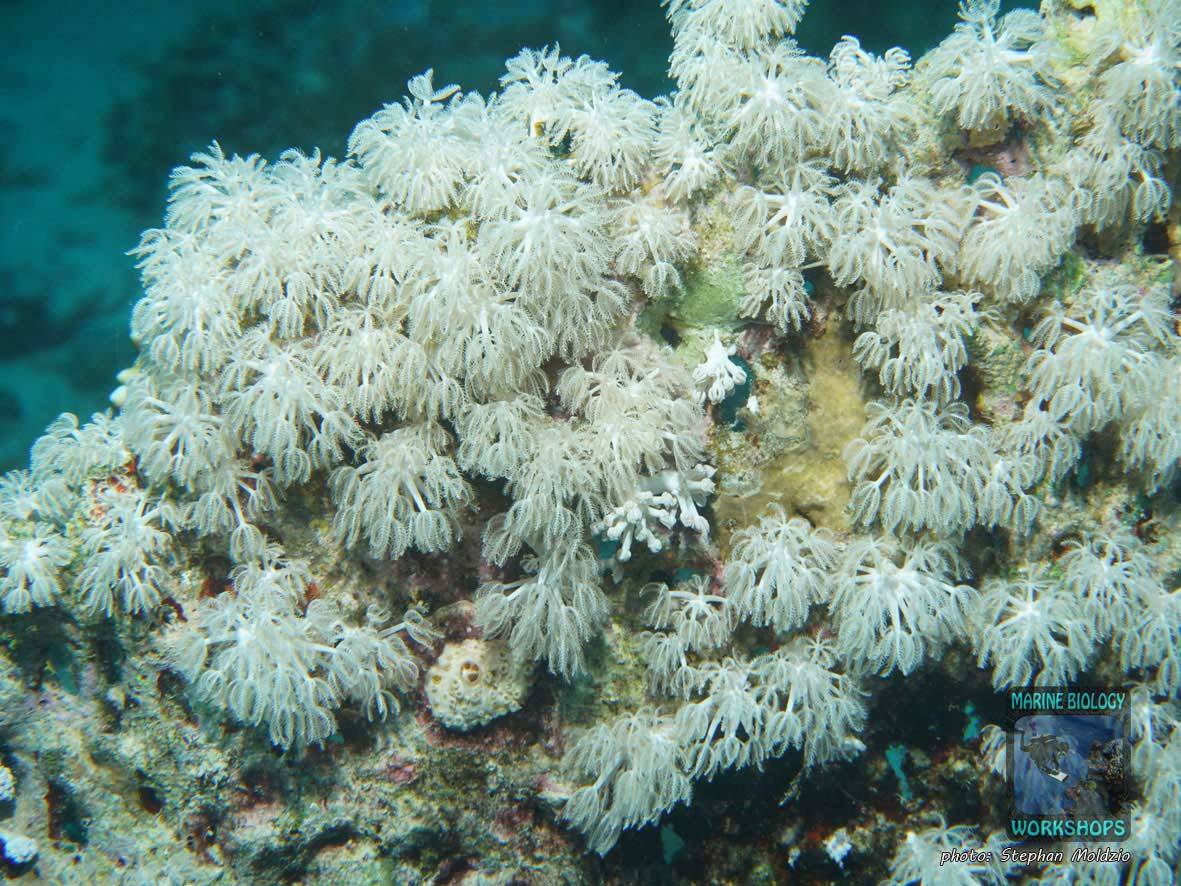

Soft Corals – The Eight-Tentacled Anthozoans

Leather coral, soft coral, and gorgonians, as well as sea pens (Pennatulacea) and the blue coral (Heliopora coerulea), belong to the eight-tentacled anthozoans (Octocorallia).

They always have eight, mostly feathery tentacles and, with a few exceptions (e.g., organ pipe coral Tubipora, blue coral Heliopora), do not form a calcareous skeleton, but only various skeletal elements, such as calcareous spicules.

Some groups possess symbiotic zooxanthellae, which are usually pastel beige-brown in color and found in shallower waters. The soft coral and gorgonians shown here all contain zooxanthellae and belong to the genera Rumphella, Litophyton, Sclerophytum, Anthelia, and Xenia.

Some groups do not possess zooxanthellae and are often very colorful. Because azooxanthellate soft corals and gorgonians rely solely on capturing phyto- or small zooplankton, they require a continuous current and dominate in deeper waters.

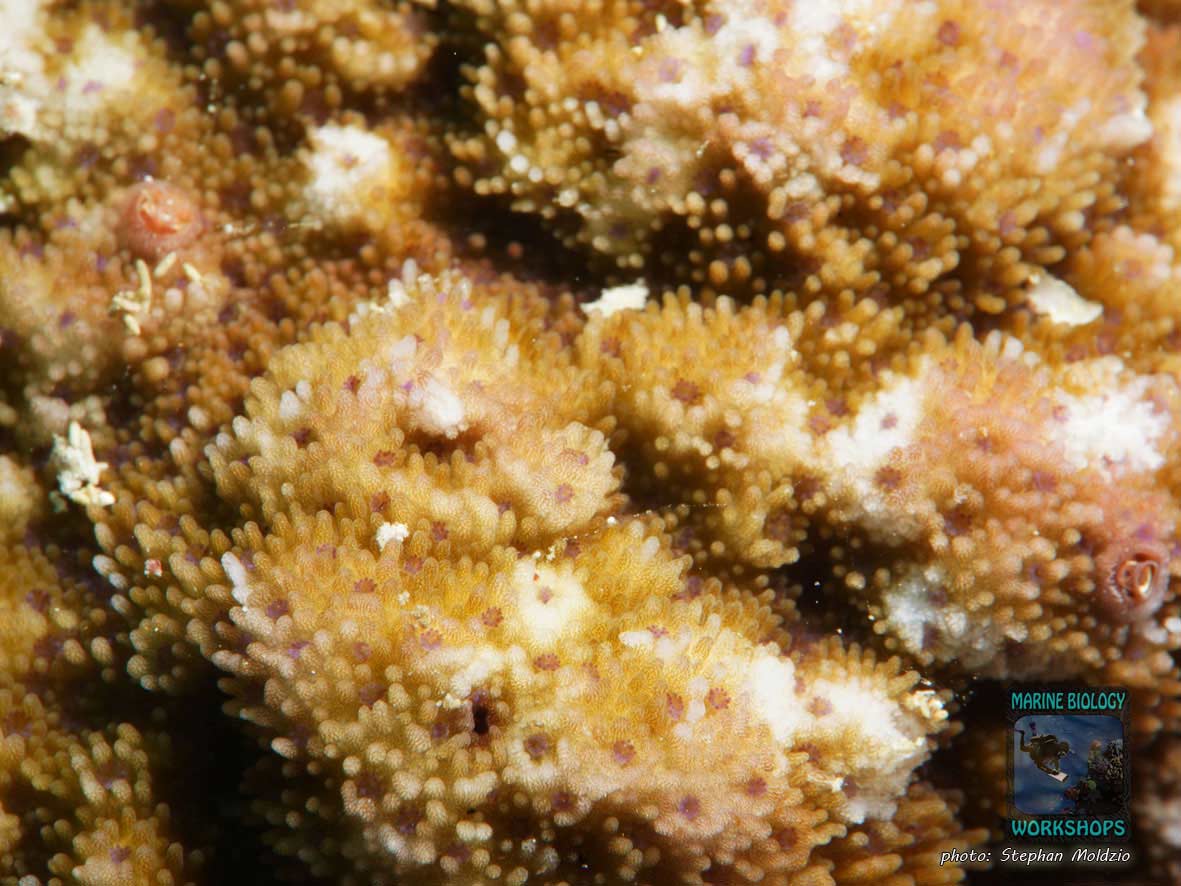

Macro photos and coral identification

The stony corals (Scleractinia) have six-fold symmetry in terms of the number of tentacles and septa (septae and costae). For genus- and species-level identification, the delicate skeleton, the structure of the coral cups (corallites), and the development of the corallite walls, septa, and other skeletal elements are important. Reliable genus-level identification can be achieved using the Indopacific Coral Finder:

What type of walls do the corallites have? Separate, shared, or indistinct walls? Are there conspicuous growth forms or skeletal structures? How large are the polyps?

Here are some close-up photos of various corals.

Trip to Elphinstone reef

On a free day between the surveys, we made a trip to the world-famous Elphinstone Reef. This platform reef, located about 9 km offshore from the coast, has several plateaus on its north and south sides and drops to about 100 m depth along its steep walls. Due to the strong, continuous currents that bring plankton, the area is densely covered in soft corals and gorgonians, and is home to an extraordinary abundance of fish. The reef is surrounded like “onion layers” by countless anthias, and further out by fusiliers and trevallies. Depending on the season, sharks and other large fish can regularly be seen in the open water. There were also many damaged corals on the reef crest due to bleaching, but the reef seemed less affected overall by previous coral bleaching. At the reef crest, we observed many intact corals, including sensitive table corals and plate fire corals.

Excursion to Marsa Abu Dabab

We also made a trip to Marsa Abu Dabab, a wide bay known for its large seagrass meadows, as well as its resident green sea turtles and dugongs.

We dived from the northern corner along the reef into the bay and then over the sandy bottom.

Here, we observed a sleeping green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) and many other special inhabitants of the sandy bottom, such as the yellowmargin triggerfish (Pseudobalistes flavimarginatus), the boxfish (Ostracion cubicus), and various emperors (Lethrinidae).

The sandy bottom and seagrass meadow habitat, which is closely linked to the coral reef, is of great ecological importance. Here you will find a very special community of organisms: starting with seagrass and invertebrates living hidden in the sand, to sand diver (Trichonotus sp.), to guitarfish, turtles, and dugongs.

Trip to Long Canyon

The dive site Long Canyon is a reef near Marsa Abu Dabab, somewhat offshore.

The special feature is that you can dive through the tunnel system running through the reef. The winding tunnels are not completely closed at the top, allowing enough light for orientation and providing the option to surface if necessary.

This makes it a relatively easy but spectacular dive with a real “cave feeling.”

In the shaded areas, many cave dwellers live, such as soldierfish (Holocentridae) or sweepers (Pempheridae). Outside the canyon, we encountered a strikingly red bubble-tip anemone (Entacmaea quadricolor), inhabited by a pair of Red Sea anemonefish (Amphiprion bicinctus).

Reef Check Surveys at Marsa Nakari

On the penultimate day, we also made a trip to Marsa Nakari to conduct the two planned Reef Check surveys at the house reef. We left Marsa Shagra in the morning, conducted the survey at Marsa Nakari north before noon, and at the south reef in the afternoon. While laying the line, Reef Check scientist Stephan Moldzio came across a rare, cryptic stony coral species – Stylocoeniella armata.

Because this coral is not particularly conspicuous or attractive, it is probably mostly overlooked.

If you search extensively for something and cannot find it, this probably means that it is rare! This is another reason for coral fans to visit Marsa Nakari.

In July 2024, Stephan carried out detailed monitoring at Marsa Nakari, in addition to Reef Check surveys. A flood in December 2023 had damaged parts of the reef, particularly the area close to the bay’s shoreline. This monitoring aimed to investigate the impact of the flood and the 2023 coral bleaching event on the reef’s condition and the corals.

This year, Stephan conducted several photo documentation dives on the north and south reefs of Marsa Nakari.

Another extensive monitoring programme is planned for July 2026, 2.5 years after the flood. Following this, a report will be compiled on the impact of the flood and the 2023/24 coral bleaching event on the house reef within Marsa Nakari, as well as on the development and regeneration that has occurred between July 2024 and July 2026.

A brief explanation: these periodic flood events, which have occurred for thousands of years, are the reason for the numerous natural bays (‘Marsa’) along the Egyptian coast. The sudden influx of large quantities of fresh water and sediments causes corals to die, especially within the bay. This prevents the bay from gradually ‘growing up’ and filling in. Otherwise, there would only be a continuous fringing reef along the coast.

A big thank you to Red Sea Diving Safari and the entire team for their long-standing support and excellent cooperation!

Many thanks also to the Reef Check team and all the reef checkers who helped collect important data on the health of the coral reefs this year.

We look forward to seeing you again at the next surveys!